by Carli Scalf

by Carli Scalf

Imagine a sea of Ball State students gathering in front of the Arts Terrace at the David Owsley Museum of Art, not for graduation, but demonstration. At 10:30 a.m. May 7, 1970, a student yelled into a microphone, “Ball State, where are you?”

The rallying cry came from then-junior Angelo Franceschina, according to the next day’s edition of The Daily News. Franceschina was kicking off the largest Vietnam War strike to occur on Ball State’s campus. Before this event, Cardinal representation on the Vietnam issue was scarce.

History professor Anthony Edmonds, who was teaching on campus during the 1970s, in an email, recalled protest in the fall of 1969 included “only a couple of hundred people” with very few viewers.

Mary Posner, who was president of Ball State’s chapter of the Vietnam Moratorium Committee, said the group often faced opposition and only had a small core of dedicated students.

With this in mind, the question Franceschina asked the morning of May 7 was fitting: where, indeed, did Ball State stand?

As thousands showed up in front of the Arts Terrace throughout the day, it was clear many students had been newly awakened to the issues the war presented.

The killing of four Kent State students by the National Guard at a campus war protest just days before on May 4, at a campus only a little more than four hours away, had brought the conflict too close to home.

Finally, students were seeking answers.

Prior to the Kent State shootings, the bulk of Ball State’s demonstrations against the Vietnam War came from its scrappy but determined chapter of the Vietnam Moratorium Committee (VMC).

The chapter was founded by Posner in the fall of 1969 after she met other students starting VMC chapters at a National Student Congress Convention in El Paso, Texas. The idea appealed to her already-growing interest in the conflict; earlier that summer, she had been fired from an office job for posting a news article about napalm on the company bulletin board.

The original sign-up sheet for Ball State’s VMC chapter, which Posner still has in her records, included 98 names; however, she said she remembers a much smaller group of students who were consistently involved in planning events. Alumnus Mark Sharfman, a member of Ball State’s VMC chapter, remembers about 20 students in this core group.

“Although we were small, the people involved were really hard workers,” Posner said.

While the national VMC was encouraged by Ball State’s protest activity, much of campus was hostile or indifferent to its efforts.

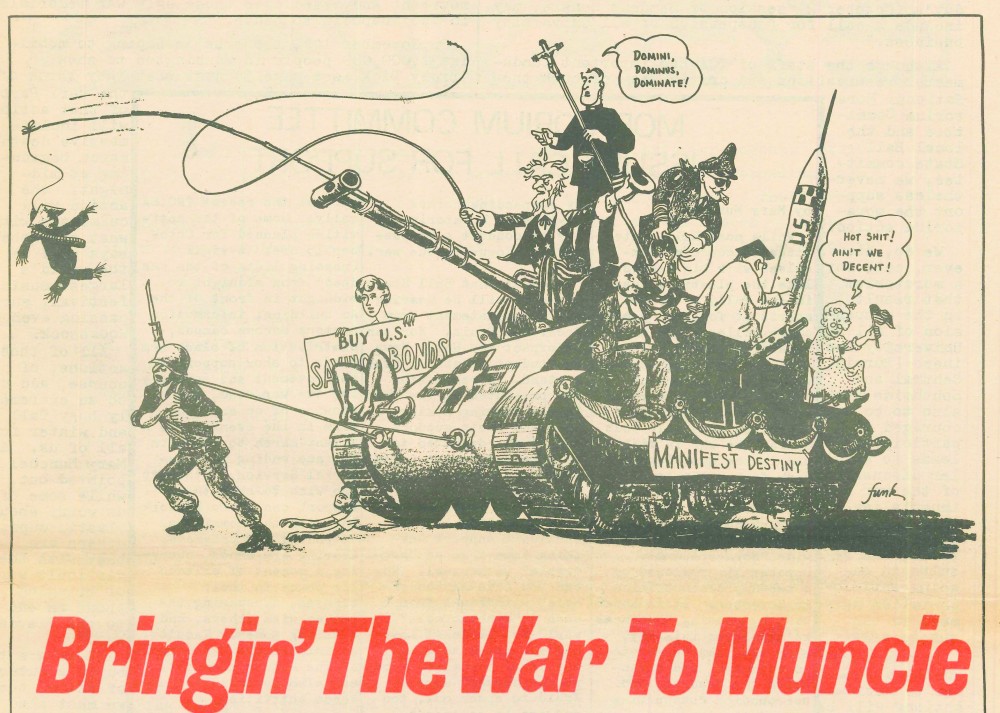

“We got a lot of opposition from all kinds of people,” Posner said, pointing especially to the frequent criticism the group received from The Daily News. Though The Only Alternative, a progressive underground newspaper on campus at the time, did give the VMC ample and often supportive coverage, Posner also remembers being criticized by the publication for not being “radical enough.”

Perhaps the most controversial event held by the VMC was a protest that included the reading of the names of all the American soldiers who had died in Vietnam, held on campus Oct. 15, 1969. The event inspired a counter-protest, a public statement of opposition from the University Veterans and at least three Daily News editorials commending the Student Government Association for voting to not support the protest.

“I strongly disagreed with that, because it was my belief that we were trying to prevent future people from dying in Vietnam, and to me, that was very meaningful,” Posner said.

Despite the hostility, the VMC persevered, and set a precedent of avoiding violence during protests and demonstrations.

“We had a decent pipeline from the VMC to the university administration, and we made promises that we intended to and did keep to prevent violence,” Sharfman said.

After a year of ups and downs, the national VMC disbanded in April 1970, and Ball State’s chapter followed suit. On April 29, 1970 Posner announced at a luncheon that the VMC was dissolving and joining the New Left Coalition, which combined many progressive groups on campus, including the Other Alternative and the Black Students Union.

Five days later, the National Guard opened fire on a student protest at Kent State University, wounding nine and killing four students.

On April 30, President Richard Nixon announced the expansion of military forces in Vietnam into Cambodia. The decision sparked immediate protest around the country, including among college students at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio.

A large anti-war protest was held Friday, May 1, 1970 on the campus. After the ROTC building was burned down on campus, on May 2 the mayor of Kent declared a state of emergency and requested Gov. James Rhodes send the Ohio National Guard to restore order.

In 1970, Ball State and Kent State were, in many ways, similar schools. Both were in the Mid-American Conference conference, both were in the midwest, and both were known for having “town and gown” tension between the university and the conservative, blue-collar towns that surrounded them.

Despite these similarities, Ball State’s level of protest activity was relatively low. In the book “Ball State: An Interpretive History” by Edmonds and Ball State history professor Bruce Geelhoed, this difference between Ball State’s protest activity and other schools is noted: “Ball State University experienced a relatively small measure of the student discontent that marked many other American campuses in the late 1960s and early 1970s.” In contrast, Kent State’s level of protest activity was intensely high.

Ball State history professor Ed Krzemienski said a possible explanation for the difference in protest activity was Kent State’s tie to the metropolitan areas of Cleveland and Akron. While the land between Muncie and Indianapolis is mostly rural, the area between Kent State and its two neighboring cities is populated with towns. This made the distance between the university and the city, especially in terms of expanding anti-war sentiment, feel much smaller.

Religious influence is another possible explanation for the differences between schools.

Ball State’s student body tended to have more of a Protestant influence, which aligned many students with conservative ideals, while Kent State’s had a greater Catholic influence, which aligned many students with left-wing ideals (thanks, in large part, to the recent election of the first Catholic president, John F. Kennedy, by the Democratic Party).

Posner remembers the Newman Center, a Catholic church close to Ball State’s campus, being one of the only consistent supporters of the VMC’s protest activity.

The cosmopolitan and religious influences, combined with an intellectual and engaged student body, made Kent State fertile ground for student protests. Ball State’s isolation from larger cities and its differing religious influence made it less of a political hotbed.

“It was a perfect storm,” Krzemienski said of the Kent State environment.

After being called in by the governor, the National Guard arrived over the weekend and was present the following Monday, May 4, when students returned to campus and gathered for an anti-war protest at noon.

According to Ohio History Central, National Guard members fired tear gas at the crowd of protesters, which they began throwing back at the guardsmen. Reportedly fearing for their life, guardsmen armed with rifles and bayonets began to shoot at the crowd, killing four students and wounding nine; two of the students who died were not participating in the protest.

The incident sparked outrage everywhere, but especially on college campuses. Ball State’s reaction was strong, both because of the shocking nature of the event and because of Kent’s proximity to Muncie. Ball State’s president at the time, John J. Pruis, released an impassioned statement on May 5:

“The tragic events at Kent State University have brought to all of us a sense of grief and a feeling of deep frustration bordering on despair. We grieve because four students lost their lives and we know not why. We did not know them but in their despair we identify with them. The senseless loss of these four young lives bespeaks a deep cancer in our society which must be healed if we are to endure.

We are frustrated because we are painfully aware of these monstrous problems but we are at a loss to know how to bring our best thoughts to bear in their solution and obviously we as a nation are still a long way from finding the right answers.

What of the future? I continue to trust that the educational community can and will point the way. We must not give up, rather redouble our efforts to seek out the root causes and to propose solutions which will be effective and which will also find acceptance. My hope is that all of us will be rededicated to the grew purpose which brought us together for the improvement of ourselves and thereby society."

The show of support from the president for education around the issue of the Vietnam War made an impact. Students who had previously been disinterested in the war were finally paying attention.

“It was an incredibly profound experience for those of us on Ball State’s campus,” Sharfman said of the Kent State shootings. “It was just this amazing tragedy that should have never happened.”

The new level of interest in the conflict allowed demonstration organizers to secure a level of support they hadn’t previously. Sharfman fought for and succeeded in winning SGA approval of a campus-wide “teach-in” event to be held in front of the Arts Terrace on May 7, 1970.

The goal of the “teach-in,” Sharfman said, was to educate the student body on all sides of the Vietnam conflict and get them to really think about the motivations behind the war. The event included speakers from both sides of the issue and drew a crowd of thousands — students and professors alike.

Though the VMC had dissolved just days before the “teach-in,” was organized, its former members participated in the event and were glad to see a larger part of campus finally engaging in the anti-war movement.

“Kent State happened one state over from us, on a similar sort of campus, and four students were killed,” Posner said. “I think it just really hit home.”

In addition to the speakers, a memorial service had been scheduled for 4 p.m., which prompted a group of students to stage a “sit-in” in front of the Administration Building to request all American flags be flown at half-mast in honor of the Kent State students who had died, according to “Ball State: An Interpretive History.” President Pruis agreed within 20 minutes.

Though Geelhoed and Edmonds called this demonstration “quiet, peaceful and extraordinarily mild,” the mere presence of thousands of previously inactive students and faculty at an anti-war event marked a change in Ball State’s perception of the war.

Forty-eight years after the Kent State shootings and the protest that followed, Posner and Sharfman expressed the hope that today’s students can learn from the past and continue using their voices to protest about issues concerning war involvement and student safety.

Both were struck by the recent protests started by high school students from Parkland, Florida, after a shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School left 17 students and faculty members dead and 17 more injured. Their activism gave new energy to the gun control debate and put student safety at the forefront.

“While the tragedy that occured in Florida was sickening,” Sharfman said, “the shootings have mobilized a huge part of the young population, and [the protest activity] warms my heart, because it’s so close to what we did back then.”

Posner and Ball State history professor Michael Doyle are in the process of planning an event that will make sure the Ball State and Muncie community don’t forget about the impact of student protesting during the Vietnam War era.

The event, which is scheduled for October 2019, includes two parts; a reunion of Ball State’s chapter of the Vietnam Moratorium Committee and a day-long conference focused on the historical impact of the Vietnam anti-war movement. The date will mark 50 years since the first VMC protest at Ball State, lending the two-day commemoration a retrospective feel.

“[The conference] attempts to widen the historical frame of the protests, the experience of Vietnam at 50 [years old], but also ties to the people who are actively engaged in these very same issues today for a very different set of circumstances,” Doyle said.

Panel topics will include the accomplishments and failings of the anti-war movement and what today’s activists can learn from protesters of the past.

Both Doyle and Posner said they hope the conference starts a conversation and inspires action among students and community members. More than that, however, the conference will ensure that Muncie will not forget the protests of the VMC, nor the strength of Ball State’s reaction to the Kent State tragedy all those years ago.

Contact Carli Scalf with any comments at crscalf@bsu.edu or on Twitter @carliscalf18.