Brynn Mechem and Mary Freda // Story Kaiti Sullivan, Madeline Grosh and Rachel Ellis // Photography Michael Himes and Emily Wright // Development and Design Created April 26, 2018

Brynn Mechem and Mary Freda // Story Kaiti Sullivan, Madeline Grosh and Rachel Ellis // Photography Michael Himes and Emily Wright // Development and Design Created April 26, 2018

In 2018 alone, 610,000 Americans will die from cancer. For Cancer Control Month, The Daily News shadowed and sat down with Ball State professors to reflect on their past and continuing journeys with cancer.

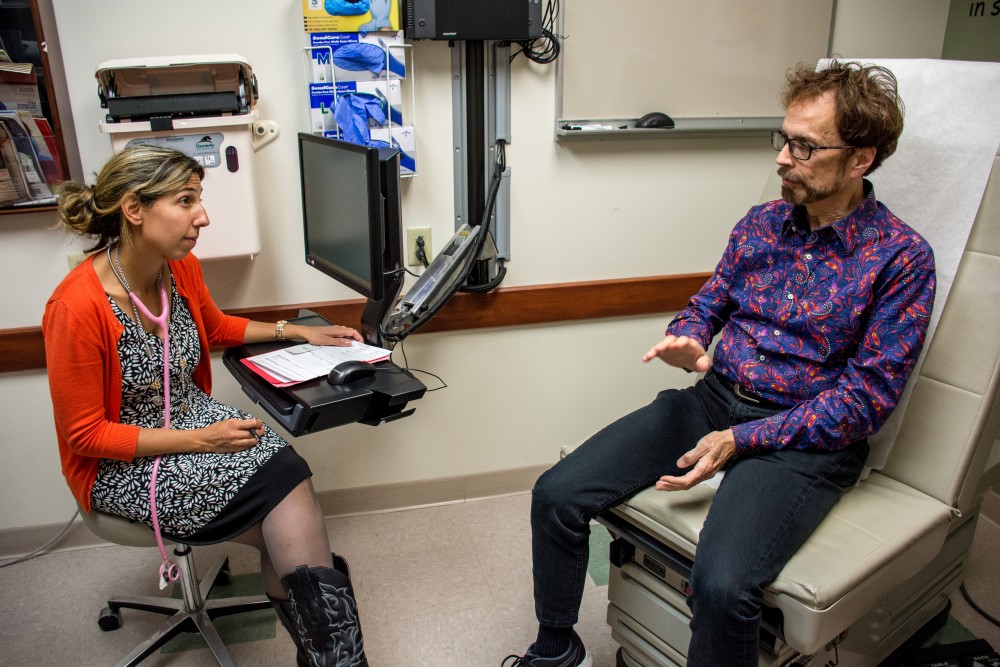

In the brisk October morning, Stan Sollars quickly walked through the automatic sliding glass doors into the almost too-bright lobby. He took a seat in the pale blue and green chairs that are meant to be comforting, but the lumps didn’t help overcome the anxiety that comes with waiting. He put his arm around his nervous wife. “It’s going to be fine,” he said. “We’ve done this before.”

He walked through the labyrinth that was Indiana University Health University Hospital, never even looking where he’s going. He clutched the “football,” the giant accordion-style folder that houses all of his medical information to his side. He smiled and gave an animated hello to the receptionist, greeting her like he would an old friend. She smiled, the blue light from the computer screen reflecting in her glasses.

She knew him.

They all knew him.

They had seen him more than 40 times in the last three years.

He took a seat in the familiar chairs. He clutched a large water bottle that he purchased in anticipation for the day’s events. He explained what his body was about to endure.

“I have to drink a liter of water so that I can flush out all of the radioactive stuff as quickly as possible,” Sollars said.

A liter may seem like a lot, but to Sollars, a couple extra trips to the bathroom is a small price to pay for his life. The radiologist called him to the back. He walked past a patient left in the hallway, too weak to lift his head off the pillow. In a cold room, he showed off the machine that would soon send an army of X-ray waves and radiation into his body, scanning for any signs of a foreign object. Sollars lay still, the machine whirring around him, waiting for any signal of something that could again consume his life.

In the reception room, his wife fought back the tears that were perched just behind her lids, threatening to tumble over the edge.

“There's always a fear that it will come back,” Allison Pareis, Sollars’ wife, said. “That's why I always get really antsy on scan days. I mean, he's fine and I don't have any reason to really think that there's a problem, but it's a human thing just to have that little thing that says, ‘What if, what if, what if.’”

Sollars, a Ball State lecturer of telecommunications, isn’t alone in his fight. He is just one of the 1.8 million U.S. citizens who get a cancer diagnosis every year, according to the National Cancer Institute. Of those, 67 percent will still be alive five years down the road, up 17 percent from 1974.

Of the estimated 1.8 million, nearly 610,000 will die.

In the waiting room, Pareis nervously thumbed through the pages of a book that she never got the chance to read. Her right knee was bouncing up and down as if she were calming an imaginary child, and even as she talked, she couldn’t peel her eyes from the door. When he finally came back, she went through her routine checklist.

“How did it go? How do you feel? Did you finish your water? We need to go upstairs now.”

As they made their way back through the never-ending maze, the couple explained life during treatment. Sollars initially had surgery to fix an issue with his esophagus, but during the surgery, doctors found a tumor. When Pareis found out the surgery meant something more, she didn’t handle it very well.

“That first day, he was so heavily drugged, we were all sitting in the room waiting for the ER doctor to come and explain to Stan because nobody had told Stan yet. I was just trying to hold myself together so I couldn't say it,” Pareis said.

“So they have the ER doc explain it to him, and at that point my parents and I are just like stunned. I’m really just upset, like, I had been screaming and everything. Stan was like, ‘It'll be OK. It'll be totally OK. I'll be fine, I already know that I'll be fine.’”

It is this mindset Sollars would later say got him through.

“You have to put on horse blinkers, like you would put on a race horse, because if you’re distracted one way or the other — ‘What about Fred’s cancer,’ ‘What about Jane’s cancer?’ — that spreads,” Sollars said. “I had to focus on my cancer and survival.”

A white and teal wedding

It was on her 30th birthday that Kendra Zenisek, lecturer of kinesiology and coordinator of physical fitness, got preoperative testing to see if she had cancer. She found out two weeks later she did.

“Thirty wasn't a great year,” Zenisek said. “I didn't really enjoy 30. Turning 30, most people are like, ‘Oh, it's just 30, it sucks,’ and I was like, ‘No, 30 is different for me.’”

For the newly-engaged woman, the diagnosis was worse than she could’ve imagined. She had adenocarcinoma, a more aggressive type of cervical cancer.

According to The National Cancer Institute, adenocarcinoma is when cancerous cells skip around to various parts of the body. This type of cancer is much harder to treat than squamous cell carcinoma, which tends to be much more isolated.

“The recommended path of treatment at that point in time coming from the doctor that I had was complete hysterectomy, which means ovaries, uterus — everything,” Zenisek said. “At that age, I was like, ‘What if I want kids or what if I want a family?’”

After being recommended to doctors in Indiana and Georgia, Zenisek found a doctor at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City that could perform a surgery that would still allow Zenisek to have a child through a C-section delivery. However, during surgery, doctors found the lesions had spread further than they first thought and Zenisek had a complete hysterectomy.

The complications didn’t stop there, though. A few days after the initial surgery, Zenisek developed a bowel restriction and underwent another surgery, keeping her in the hospital for another three weeks.

“The thoughts kind of at the time were, ‘What did I do wrong,’” Zenisek said. “I did everything that I was supposed to. I worked out regularly, I ate healthily, I tried to take really good care of myself — I did everything right.

“You start to think, ‘I'm a good person and I do everything I'm supposed to do,’ and then all the sudden you get hit with a diagnosis.”

After returning to Muncie, Zenisek’s doctor recommended she undergo six to eight weeks of chemotherapy, including daily radiation.

“During that second week of radiation, I had massive complications,” Zenisek said. “I couldn't keep anything down. I was really dehydrated. I ended up back in the hospital and what they determined at that point was that the radiation had burned my intestines to my abdominal wall.”

So, Zenisek went through another surgery and quit chemotherapy and radiation.

“I had to eat through a tube in my arm, which is not a diet plan that I recommend,” she said. “I lost about 20 pounds during the whole process, but fortunately at that point, I was still in the process of getting ready for a wedding, and I was like, ‘I don't want to lose my hair,’ and I was fortunate enough that I didn't.”

Zenisek’s final surgery happened in October 2009 and she and her fiance were married the following May. Zenisak didn’t have to move her wedding day and even got inspiration for her journey — she added teal, the color for cervical cancer, to her wedding dress.

And while it has been nine years since she was diagnosed, Zenisek said there is still a fear that the cancer may come back.

“You've been diagnosed once, you've gone through the process and you know what it feels like and you know how hard it is not only on you, but on your support system because you see it in their face,” Zenisek said. “You know the challenges and so every time you go back for that test, you question, ‘Am I that strong enough to do it again,’ and ‘Can I put my family and my loved ones and my support system through that again?’’

A routine check up

It was 1995 and Peggy Fisher was 36 years old. It was then, she discovered her mother had breast cancer. Nine months later, her mother died.

After that, she and her three sisters made it a habit to get routine mammograms. But in 2001, Fisher’s routine turned into a months-long relationship with breast cancer.

“I kept doing everything that I had done before,” Fisher said.

She went through chemo, had three lumpectomies — a surgery where only the tumor and some surrounding tissue are removed — and the cancer was gone — or so she thought.

Fourteen years later, Fisher found herself in the doctor’s office for another routine mammogram. She got the call 10 minutes before her next class that day.

“I got the phone call on my phone and I recognized the number and I went over to Beth Messner’s office and put it on speakerphone,” Fisher said. “You just go into fight mode. It’s like, ‘OK, what do I do next? Let’s get this going so I can get it over with.’”

The cancer was back in the same breast. This time it was more aggressive and a completely different chemical makeup.

She had a simple mastectomy — the removal of an entire breast, including the nipple, the areola and skin according to American Cancer Society — and the doctors brought out the “big guns” with chemo again, and this time it was harder, she said.

“You lose a boob and what does that do to you? And I never really thought that it mattered. I was like ‘OK, well no big deal,’” Fisher said. “Physically it didn’t really matter to me that much.”

During her second round with cancer, Fisher was teaching a fall 2015 immersive learning course in collaboration with Little Red Door — a local nonprofit that provides cancer patients with resources.

Fisher recalled leaving class to throw up and sometimes not coming in at all because she physically couldn’t. So, she would Skype in and her students continued to show up.

“Those students got more than they bargained for that semester. They shaved my head, they came to chemo with me. They came to doctor's appointments with me. They helped me pick out a fake boob,” Fisher said.

Despite the support from her students, there were times she felt others thought she invited the disease into her body. “It’s your diet,” they would say.

“That frustrated me that people thought I was doing something lifestyle-wise to cause my cancer,” Fisher said.

In spring 2016, Fisher started exercising with her son, Adam, who was training to serve in the military.

“I was trying to do a lap around my neighborhood to get my blood flowing and I was trying to detox and get all the crap out of my system and he just came up real slow behind me and said, ‘Mom, let’s just run down to the end of the street here, you can do it, we’ll just go slow,’” Fisher said. “So I did it, and the next time I did a little more and next time I did a little more.”

Adam, would complete training exercises on the patio, like push ups, and she would join him, but he never let her do too much, she said.

Now, Fisher said she still deals with, and will forever, some side effects like pain in her feet, legs and hips and “chemo brain,” which affects a person’s ability to remember certain things, complete tasks or learn something new, according to American Cancer Society.

The hardest part for Fisher, though, was and still is the emotional recovery.

In fall 2016, Fisher shared a PowerPoint presentation with her students, which showed a photo of her after with a newly-shaved head in the wig room at Little Red Door — she had to send her students home that day.

“I've looked at these slides 100 times. It was no big deal, but as soon as it popped up on a big screen and I saw [it] larger than life, I had to stop class. I just stood there and bawled,” she said.

One in a thousand

“I was the first person who noticed a lump,” said David Sumner, professor emeritus of journalism.

That lump was found after the then 64-year-old came home from a June 2010 run. Sumner waited two weeks before seeing a doctor. After a needle biopsy, his suspicion was confirmed: breast cancer.

It was a Thursday. By Monday, Sumner had an appointment for a mastectomy.

According to the American Cancer Society, 1 in 1,000 men will be diagnosed with breast cancer is his lifetime. In 2018, American Cancer Society estimates 2,550 men will be diagnosed with breast cancer.

Of those, 480 will die.

“I think the experience of cancer is definitely not a death sentence … It also offers an opportunity to have a deeper and a richer life than you've ever had before,” he said. “I don't want to call it a blessing, but you can use that experience of suffering to make yourself a better person and a more caring person.”

When he was diagnosed, Sumner was a magazine-track professor. He taught students how to improve their writing and the technicalities of publishing, but he also gave students an up-close-and-personal look into male breast cancer.

Every Wednesday during the fall 2010 semester, Sumner, who never missed a day of class, would go to his 5-hour chemotherapy appointment in the morning and teach a class in the afternoon — through the chemo, hair loss and diet changes.

“I just wanted people to continue to relate to me like they always had,” Sumner said. “I didn't want people [to] start seeing me as a victim or starting asking a lot of questions about my treatment, so I just continued acting like I always had.”

Instead of taking the diagnosis as a death sentence, Sumner changed his diet and continued running. He cut out red meat, dairy and took daily supplements to be an active part of his cure.

Since 2011, Sumner, now in his 70s, has committed to running a half-marathon every year including the Kentucky Derby Festival miniMarathon and the Indianapolis 500 Festival Mini-Marathon — a tradition he started nine days after he finished radiation therapy.

But an active part of his cure wasn’t just about physical well-being, Sumner continued to develop his Christian faith. A woman in her 40s from Sumner’s church was diagnosed around the same time he was. They shared stories and struggles, but she died in 2015, giving Sumner survivor’s guilt, the guilt one feels when they survive something another dies from, according to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

“You know, why, why me, God?”

“I feel fortunate that God allowed me to continue to live and I felt like, ‘Well, he must have more for me to do,’ but I'm just so sad that not only her, but there was another woman in our church who died just from breast cancer just a year before that,” Sumner said.

In the last seven years, Sumner said three women from his church have died from breast cancer.

“Sometimes I'm not sure I was the one who deserved [life],” Sumner said.

Winning the war

In another waiting room, the couple is much more relaxed. They joke and tell stories about their dogs. Various people give side-eyed glances as they laugh, something Pareis said was not uncommon for them. On chemo days, Pareis said she, along with family and friends, would play games.

“We were always up there joking around and having fun and some people are like, ‘It's chemo, why are you laughing about chemo day?’ [But] why not,” Pareis said. “You've got to have fun to get through craziness like that, so why sit and be depressed about it because it's dark enough as it is.”

Despite 28 days of back and forth trips to the hospital, Sollars only missed a couple days as an anchor for Indiana Public Radio and physical class, but on those days, he had digital lessons for his students.

“We basically told him you have to stay home. If we were to have given him a choice, he would have been there,” Pareis said. “Right before chemo, we video recorded him teaching his students by himself in the studio. He was just like, ‘They won't miss anything.’”

The couple sits in an examination room, the doctor checking his vitals. He shivers as she presses a cold stethoscope to his chest. They hold their breath as the doctor tells them the news — he is clear, a diagnosis that still makes the couple wary.

“After I got the all-clear, I said, ‘Now what do we do?’ From the time of the diagnosis up through surgery to post-op, we had definite steps,” Sollars said. “I don’t know what it feels like to be in the armed services, but I can imagine that’s what a soldier feels after they get off the battlefield.

“I won the battle, but I had to figure out a way to win the war.”

They leave the examination room triumphant. Once more, they stroll through the network of hallways, saying goodbye to the receptionist, back through the sliding glass doors and into the adjacent parking garage.

His wife points out the spot where Sollars passed out after a nasty round of chemo. It is a reminder of a scarier time, a landmark of a past battle. The couple got into their car. He pulled out of the garage and onto University Boulevard. Their biggest worry was what they were going to eat for dinner.

And for today, that was enough.

Contact Brynn Mechem with comments at

Contact Mary Freda with comments atmafreda@bsu.edu or on Twitter@Mary_Freda1.